- How a survey telescope works differently from other telescopes

- The unexpected problems the VST team had to overcome

- The scientific discoveries enabled by VST

The skyline of Cerro Paranal is dominated by the four 8.2-metre telescopes that are part of ESO’s Very Large Telescope. But these cyclopes share the mountain summit with smaller telescopes, including a 2.6-metre one: the VLT Survey Telescope (VST). Although VST takes its name from its larger neighbours, it serves a completely different purpose. Rather than scrutinising small patches of the sky in great detail, the VST constantly scans much wider areas of the sky, mapping and cataloging celestial sources, following the evolution of objects that change in time, and discovering the rare and unknown.

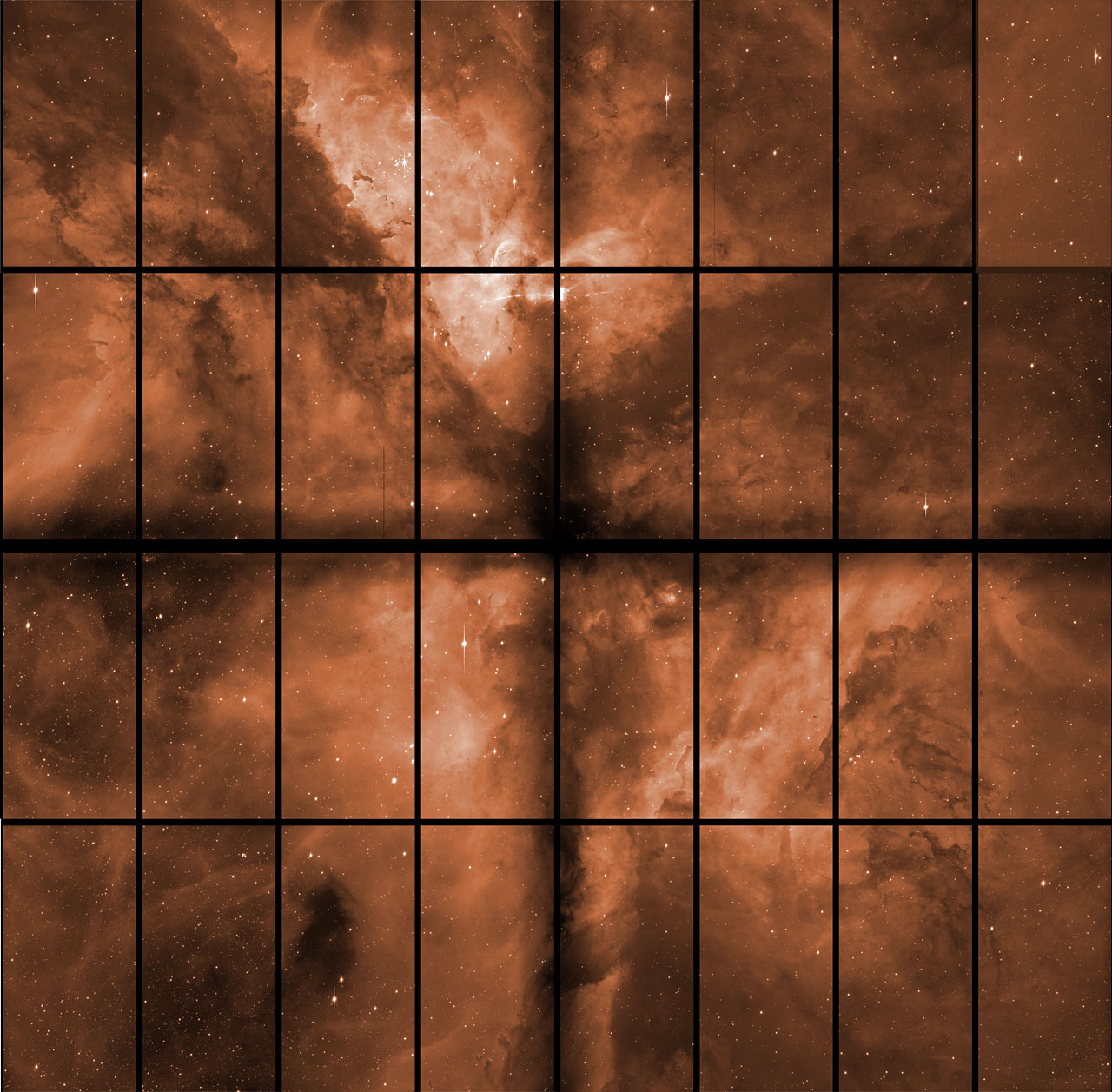

“To do this, you need dedicated instruments, with as wide a field of view as possible,” says Massimo Capaccioli, from the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). The VST hosts only one instrument, OmegaCAM, an optical camera with a field of view so large you could fit four images of the full Moon in it. OmegaCAM detects the light captured by the VST, with such good image quality that it delivers crisp images with small, round stars from corner to corner.

Astronomers find it useful to survey the skies because they can’t directly experiment with the objects they study, so they circumvent this by observing lots of them. As Enrichetta Iodice, also from INAF explains: “If you would like to have an idea of how things work in the Universe, you need to view a large number of objects or structures.” The VST and OmegaCAM were specifically designed to do that.

Per aspera ad astra: through hardships to the stars

The idea for the VST first came about in the 1990s, at the Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte in Italy (now a part of INAF), which Capaccioli directed back then.

“It looked like a crazy idea that a small institute like Capodimonte was proposing a telescope for the best observatory in the world!” says Pietro Schipani (INAF). “But you have to be brave sometimes”.

The light-polluted Italian skies led the Capodimonte astronomers to seek a partnership with ESO, allowing the telescope to be built at ESO’s Paranal Observatory, which boasts some of the darkest and clearest skies on the planet. In 1998, a memorandum was signed between Massimo Capaccioli and the director general of ESO, giving the go-ahead for the project to begin.

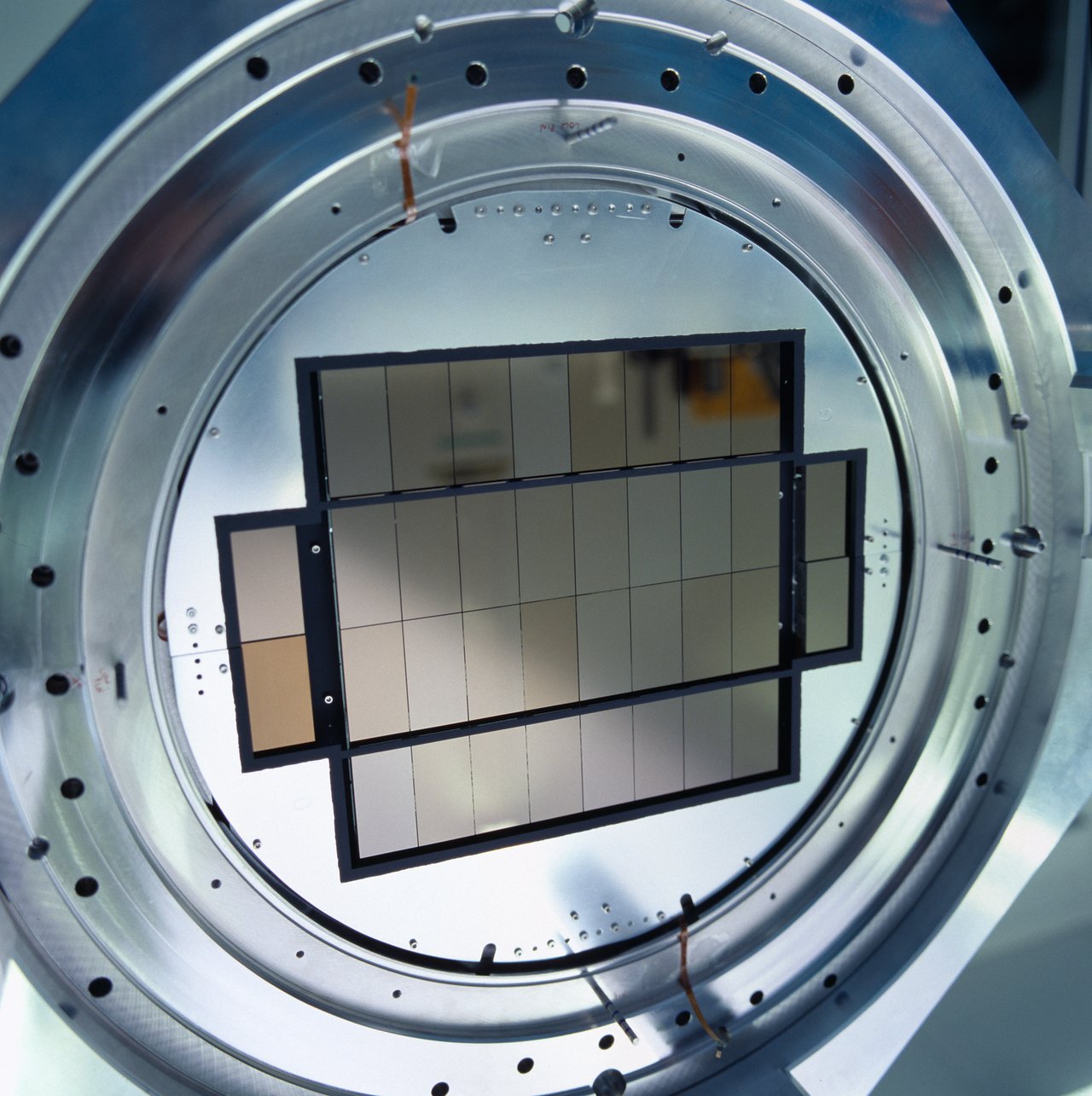

OmegaCAM was designed and built by a consortium from the Netherlands, Germany and Italy, and ESO manufactured the 268-megapixels array of detectors. The project was led by Konrad Kuijken, from Leiden University in the Netherlands; an astronomer by trade, whose scientific interest –– measuring how dark matter bends light and distorts the shapes of galaxies –– inspired him to take on the project.

Work on the telescope progressed well until 2002, when disaster struck during the transport of the VST primary mirror to Chile. Capaccioli remembers this incident with despair: “Unfortunately, an accident involving the cargo during an intermediate stop over in Central America caused destruction of the beautiful primary mirror. It was literally reduced to crumbs, the largest astronomical mirror ever destroyed.”

The whole project ground to a halt. The VST was built around its primary mirror and work was not able to continue until it was recast, causing a four-year delay and seriously damaging the morale of the team, leading to many engineers leaving the project.

But the VST’s misfortune didn’t end there. “In terms of shipping, this project was clearly cursed!” says Kuijken.

In 2009, the support system for the primary mirror was shipped to Chile. Alas, during transport seawater seeped into the box containing the mirror support, damaging it beyond repair. Schipani remembers opening the box and discovering the flood. “There were silica gel bags to prevent humidity… and they were floating in the water.” No one could have foreseen quite how humid the conditions in the box were going to end up!

After another year’s delay, every part of the telescope finally reached Paranal. It was now ready for commissioning, the stage where astronomers and engineers work side-by-side, fine-tuning the telescope and camera to ensure they perform as expected.

In particular, delivering perfectly crisp images was key. As Schipani says: “Sometimes I summarise my work by saying that I try to make the stars round and small. In Paranal the atmospheric conditions are fantastic, so all the defects of the machine that you are building will be perfectly seen on the image. So you must really take care of all the details.”

Finally, the VST was ready for first light. This moment was eagerly awaited by Capaccioli, who recalls asking the team at Paranal to “call at any time, day or night, when the photons go through and produce something.” Kuijken adds, “It was one of the most exciting times in my career, for sure.”

First light at last

In spite of all the setbacks, the VST had done it, and the first images proved it was working beautifully. Although the construction process was fraught with difficulties, the scientists and engineers working on the project found that there had been some silver linings to the long wait for the VST.

“We have learned that if you have to redo something, it often turns into an opportunity to improve it,” says Capaccioli. “If you have a second chance, the prototype will be better. Usually with telescopes, you make it once and then you don’t repeat it. In the case of the VST disasters, we used this as an opportunity.”

Scientists and engineers often approach these complex problems from opposing points of view. “Sometimes the best solution engineering wise is not the best solution science wise,” says Kuijken. “To resolve this you have to understand a little bit from both sides of the argument.” Teamwork was thus key to the project reaching its completion.

Iodice concurs: “There in Paranal it is like a big family,” she says. “You can interact with the engineers, astronomers and telescope operators all at the same levels, and each of us there has a particular knowledge and experience. Sharing this is fantastic. I always enjoyed the environment and the atmosphere. I feel I work better there.”

Now in its tenth year, has the VST achieved the goals set out so long ago at the start of its journey? Iodice, who is the principal investigator of the VST Early-type GAlaxy Survey, certainly thinks so. The survey she leads initially concentrated on the brightest galaxies in the nearby Universe, but has more recently switched focus to fainter structures, such as ultra-diffuse galaxies — objects as large as the Milky Way but hundreds of times fainter, whose origin is still unknown. “We detected these ultra-diffuse galaxies by chance in our VST surveys. The results we achieved with the VST exceeded our expectations,” she says.

The VST has helped to unravel mysteries in other corners of the Universe: it has imaged stellar nurseries in our own galaxy, mapped the distribution of dark matter in the Universe –– what first drove Kuijken into leading OmegaCAM –– and even captured the violent collision of two neutron stars. As one of the best optical survey telescopes operating in the Southern Hemisphere, the VST continues to deliver stunning images of the Universe.

The VST holds a special place in the hearts of all who worked on it, and refused to give up on it when the going got tough. “I am happy and proud of the VST as a father would be of a very successful son who has had a difficult childhood,” says Capaccioli. Schipani adds, “I have worked on the VST for a period of about ten years. It’s not like a normal project, it is really a part of me.”

Links

Biography Thea Elvin

Thea Elvin is Press Officer at The Lancet. Before she was a science journalism intern at ESO. She has completed an undergraduate degree in Natural Sciences at the University of Cambridge (UK) and a master’s degree in Climate and Atmospheric Science at the University of Leeds (UK) and is currently pursuing a career in science communications.